How I came in first on ARC-AGI-Pub using Sonnet 3.5 with Evolutionary Test-time Compute

See my code on Params: https://params.com/@jeremy-berman/arc-agi

I think ARC-AGI is the most important benchmark we have today. It’s surprising that even the most sophisticated Large Language Models (LLMs), like OpenAI o1 and Claude Sonnet 3.5, struggle with simple puzzles that humans can solve easily.

This highlights the core limitation of current LLMs: they're bad at reasoning about things they weren't trained on. They are bad at generalizing.

After reading Ryan Greenblatt’s blog post on how he achieved a state of the art 43% accuracy on ARC-AGI-Pub, I wondered if we could push these models further. Could it be that frontier models might actually possess the necessary intelligence and understanding to solve ARC? Maybe if they are poked and prodded enough, they’ll spit out the right answer.

After lots of experimenting, I got a record of 53.6% on the public leaderboard using Sonnet 3.5.1 This is a significant improvement over the previous high score (Ryan’s) of 43%.

My approach works by having Sonnet 3.5 generate a bunch of Python transform functions, testing them against challenge examples, and then using the best-performing functions to create new prompts for generating even better solutions. This process repeats multiple times, ultimately generating up to 500 functions using 31 dynamic prompts per challenge.

I was inspired by genetic algorithms and have been referring to this approach as Evolutionary Test-time Compute.

I have the LLM generate Python functions, instead of just outputting solution grids, because functions can be executed and verified for correctness (detailed in the next section) but grids cannot.

While this approach is computationally intensive compared to human intuitive reasoning, it may hint at a path forward. LLMs can compensate for their generalization limitations through scaled test-time compute guided by evolutionary principles. By generating waves of candidate solutions and using their performance to guide further compute allocation, we can efficiently explore the solution space even with limited prior knowledge. It's possible that this kind of test-time compute scaling is how Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) emerges.

The key to solving ARC may be the key to solving AGI.

This post has the following sections:

What is ARC

My Method

Architecture

Prompting

ARC and the Path to AGI

Idea for AGI

Appendix

How to Improve My Method

What is ARC

ARC-AGI is an intelligence test designed to measure abstract pattern recognition, similar to an IQ test. What makes it notable is the stark performance gap between humans and AI: while humans can readily solve these puzzles, LLMs struggle significantly. The test presents novel patterns through a few examples and then challenges the test-taker to continue the sequence, measuring their ability to identify and generalize underlying rules they've never encountered before.

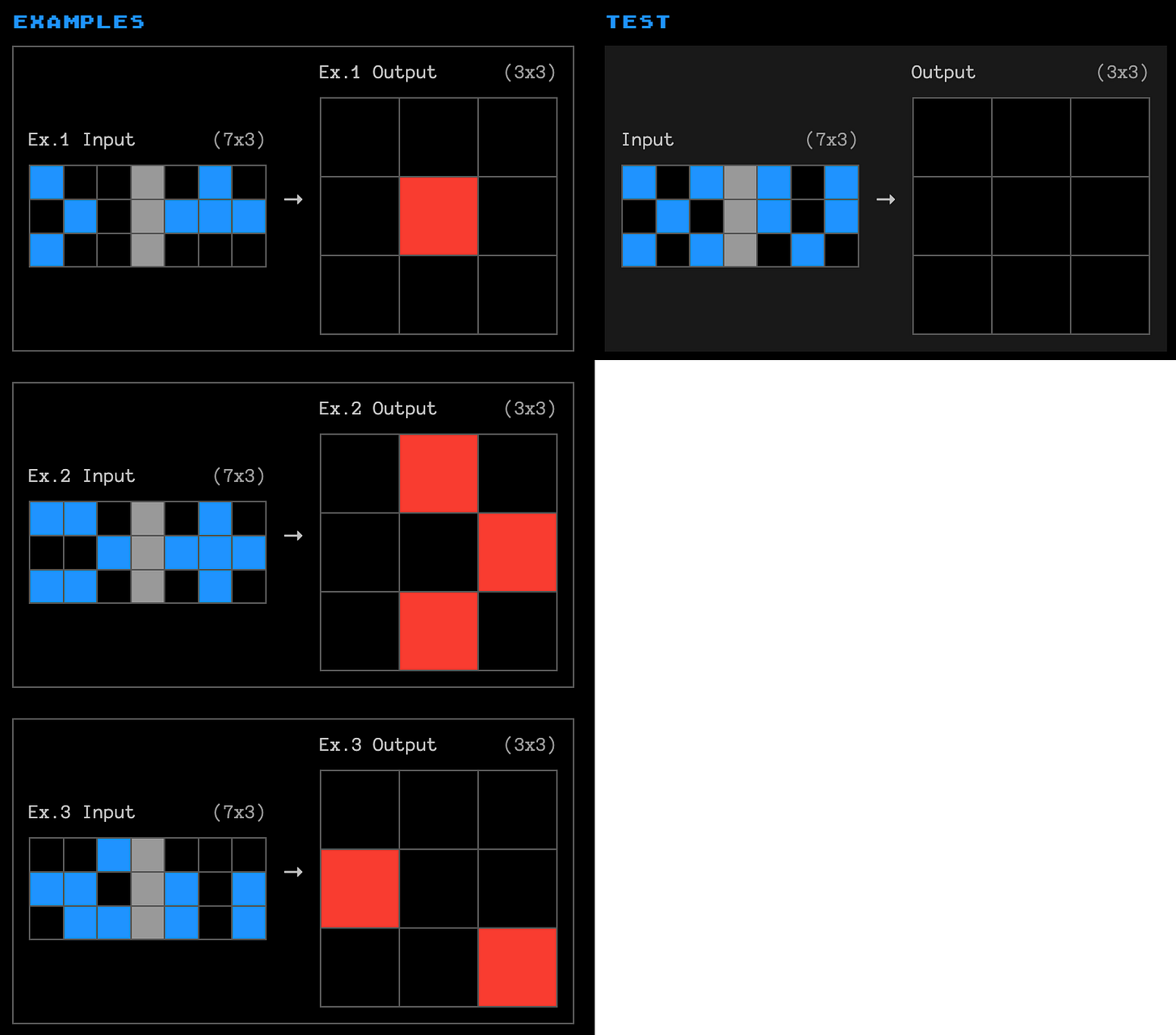

Let’s look at a real challenge. Here, you are given two examples of input/output grids and you must fill in the test output grid with the correct colors.

The solution is:

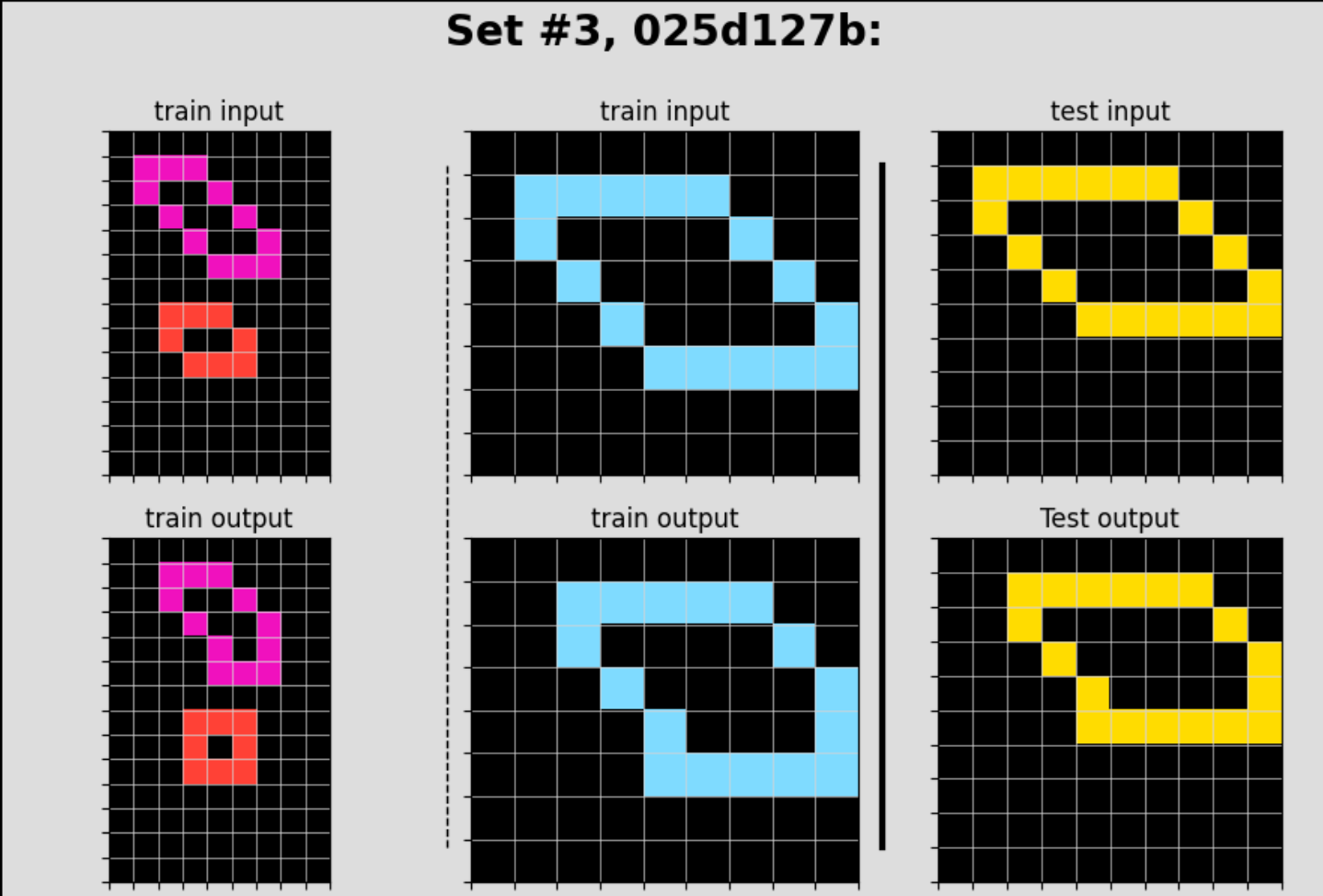

Not all of them are this easy. Here is a harder challenge:

These challenges are not so hard for humans. Humans can easily get 85% accuracy on a batch of 400 challenges. In contrast, the best LLMs get only 18%. You can find the leaderboard here.

ARC-AGI-Pub is a leaderboard for solving ARC challenges using the internet. As such, you’re allowed to use any publicly available LLM. You are given 12 hours of compute on a Kaggle notebook and $10,000 for API costs, to complete 500 challenges (400 of which do not exist on the internet).

My method gets 53.6% accuracy within the challenge requirements. This is the current public record.

My Method

This is a breakdown of how Evolutionary Test-time Compute works. I will start by describing the architecture and then describe the prompting techniques used. Full prompts are provided in Appendix Section 2, so if you are curious what exactly a “revision” or “pooling” prompt looks like, see the Appendix.

Architecture

I developed a method to solve ARC using LLMs and evolutionary algorithms. Here's how it works:

The goal is to evolve a Python function that can correctly transform input grids into output grids.

The evolutionary process follows these steps:

Initial Generation

The LLM creates multiple Python transform functions, each attempting to convert input grids to output grids

Fitness Evaluation

Each transform function is scored using the example input-output pairs provided in each ARC challenge. Since ARC provides these training examples, we can evaluate each function by running it on the example inputs and comparing its outputs to the correct answers.

The scoring has two tiers:

Primary Score: Number of complete example grids the function solves perfectly

Secondary Score: For grids that aren't perfectly solved, we count how many individual cells the function got correct

Selection & Reproduction

The best-performing functions are selected as parents

These successful functions are used to create revision prompts

The LLM uses these prompts to generate new offspring functions for the next generation

Iteration

This process repeats, with each generation of functions typically performing better than the last

Evolution continues until a function perfectly transforms all example grids, or a max generation limit is hit

The key is treating the LLM as an evolution engine: using it to both generate initial attempts and to improve upon successful approaches through guided iteration.

Figure 1 shows how the algorithm works. The red lines are LLM calls and the blue circles are the revision prompts for the n best transform functions. In this example:

Generation 1:

Start by generating 10 transform functions

Select the 5 best functions to become parents

Create revision prompts for each of these 5 parents

Generation 2:

For each of the 5 parent prompts, generate 5 new functions (Total: 25 new functions)

Select the 3 best functions to become parents

Create revision prompts for these 3 parents

Generation 3:

For each of the 3 parent prompts, generate 10 new functions (Total: 30 new functions)

Select the 5 best functions to become parents

Create revision prompts for these 5 parents

Generation 4:

For each of the 5 parent prompts, generate 3 new functions (Total: 15 new functions)

Final Selection:

From all generations combined, select the 2 best-performing functions based on their fitness scores from the example grids

Run these 2 functions on the actual test input grid to generate two candidate output grids

Submit these output grids as the solutions to the challenge (ARC accepts two attempts per submission)2

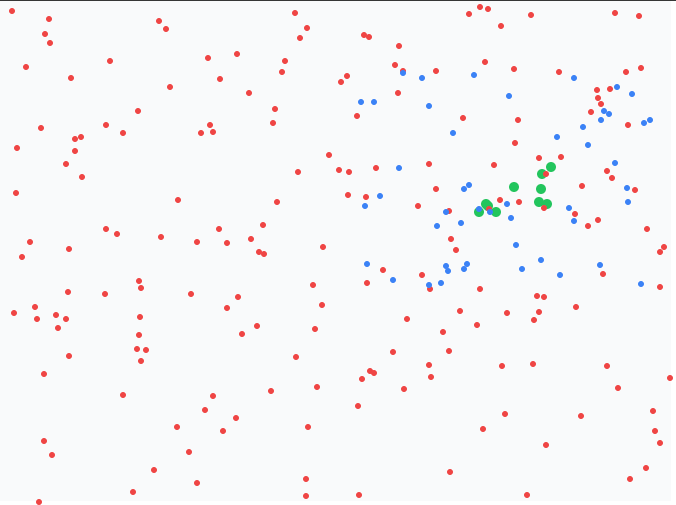

For more intuition into what is happening, imagine a vast space containing all possible transform functions. Within this space are green dots representing “correct solutions” - transform functions that perfectly solve a specific ARC challenge. Any function that falls completely inside a green dot is a valid solution.

We begin by generating 200 random transform functions (shown as red dots) spread across the solution space. These represent our first generation of attempts. They're scattered widely since we're starting with no prior knowledge.

None of our initial red dots land inside a green solution dot, but some get closer than others. We:

Select the 10 red dots closest to green solution areas (our 'fittest' functions)

From each of these 10 promising locations, generate 5 new functions. This creates 50 new functions (blue dots) that cluster more tightly around promising areas.

The blue dots are more concentrated in promising areas, but still no perfect solution. Again, we:

Select the 10 best blue dots

Generate 5 new functions from each. This creates 50 new functions (black dots) that focus even more tightly on the most promising regions.

The black dots show even greater concentration around solution areas. Finally, one black dot falls completely inside a green solution dot - we've found a transform function that perfectly solves the ARC challenge!

As with biological evolution, each generation of functions becomes increasingly fit for solving the challenge. However, this approach can encounter a significant problem: local maxima.

Consider a challenge with three example cases and these hypothetical results:

30 functions correctly solve examples 1 and 2

Only one function correctly solves example 3

No function solves all three

If we select only the top 10 functions for breeding the next generation, we'll exclusively choose functions that solve examples 1 and 2, completely missing the valuable insights from the function that solved example 3.

To address this, I developed a “pooling” approach that combines multiple parent functions into a single revision prompt. Rather than using just one parent function to generate offspring, we combine several parent functions, making sure to include at least one function that solved each example case. This creates a more diverse set of genetic material for the LLM to work with. It also creates a larger context for the LLM.

Pooling isn't always better. LLMs tend to pay less attention to longer contexts than shorter ones, and more context means higher computational costs. Ultimately, what matters is cost-effectiveness – if a pooling prompt is twice as expensive but only improves accuracy by 30%, we may get better results by simply running the cheaper single-parent prompt twice as many times with the same budget.

Given these trade-offs, my submitted algorithm runs two parallel tracks:

Traditional single-parent evolution

Pooled multi-parent evolution

This hybrid approach allows us to benefit from both methods. Figure 2 shows the final architecture of my submission:

The pooling prompts are in the red boxes.

For a description of this architecture in plain english, see Appendix 1.1.

I developed this architecture through trial and error (and vibes), though my ability to run large-scale experiments was limited by having only a few thousand dollars in Anthropic credits (shoutout to Will from Anthropic, thanks!). However, I did conduct one large-ish experiment to test whether adding generational depth could improve accuracy.

I compared two architectures across 60 training challenges, each using 200 LLM calls with Sonnet 3.5 and identical system prompts and examples:

Shallow: One generation of 200 transform functions

Deep: Four generations of 50 transform functions each

The results supported the value of deeper architectures:

Shallow achieved 70% accuracy (42/60 challenges solved)

Deep achieved 75% accuracy (45/60 challenges solved)

Of Deep's 45 successful solutions, 42% (19/45 solutions) came from generations 2-4

Most challenges that Deep solved but Shallow missed were solved in these later generations

This confirmed my intuition that allowing solutions to evolve across multiple generations leads to better results than using all attempts in a single generation.

Below are a few of the challenges Deep solved with generations 2-4 that Shallow did not solve at all:

Multiple generations prove especially valuable when many almost-correct solutions exist. In the examples above, the Shallow approach produced numerous solutions that were just one or two cells away from being correct. This is where revision prompts excel - they can identify and fix these subtle differences.

However, there's a delicate balance in structuring the generations. Like the learning rate in machine learning, you need to find the right middle ground:

Too Deep (like a low learning rate):

Each generation has too few attempts

Limited opportunity to discover novel approaches

Risk of overfitting to parent solutions

Gets stuck in a narrow search space

Too Shallow (like a high learning rate):

Solutions remain too broad

Never refine enough to find precise answers

Miss opportunities to fix near-perfect solutions

The key is finding the sweet spot where you have enough attempts per generation to maintain diversity while having enough generations to refine promising approaches:

Prompting

I'll walk through my prompting approach here, with the full prompts available in Appendix 2.

My strategy relies heavily on Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting — requiring the LLM to reason through its solution step by step before answering. This technique has proven particularly effective for reasoning tasks, which I explore more deeply in next section.

Following Ryan's methodology, I implemented one-shot prompting by providing a single detailed example of a correct solution. While I experimented with two and three-shot approaches, one-shot consistently performed best. I suspect this is because LLMs maintain better focus with concise prompts - they seem to benefit more from deeply understanding one example rather than partially grasping several.

For grid representation, I provide multiple formats similar to Ryan:

Grid dimensions

Base64 image encoding

ASCII representation

Python nested list format (list[list[int]])

Though providing all of these formats might appear redundant, testing showed that this comprehensive approach yielded the highest accuracy.

For detailed implementation, refer to:

CoT prompts: Appendix 2.1

LLM responses: Appendix 2.2

System prompt: Appendix 2.3

Complete grid representation example: Appendix 2.4

Revision prompt: Appendix 2.5

Pooling prompt: Appendix 2.6

ARC and the Path to AGI

Working on ARC has got me thinking a lot about how humans think.

One key difference between how humans and current LLMs solve ARC is that humans use deductive reasoning.

Is deductive reasoning necessary for AGI?

Deductive reasoning, or deduction, is the process of drawing conclusions that necessarily follow from given premises — if the premisses are true, the conclusion must be true. For example:

Premise 1: All humans are mortal

Premise 2: Socrates is human

Conclusion: Therefore, Socrates is mortal

Humans use deduction all the time. It allows us to reason about the world in a consistent, accurate way. When we approach ARC challenges, we intuitively hypothesize patterns and then test those hypotheses step-by-step using deduction. Mistakes occur when our deductions are flawed, but once we identify the error, we can correct it.

Inductive reasoning, or induction, by contrast, involves drawing conclusions from patterns or experience without guaranteed certainty. For example:

I’ve observed all humans die before the age of 110. Since Socrates is human, it’s likely he will die before the age of 110.

LLMs use induction — they are incapable of actually using deduction. When it looks like they’re using deduction, it’s an illusion. You can tell this by looking at the vast majority of LLM responses in my solution. They are riddled with hallucinations and obviously false statements that don’t follow from assumptions. This is different from the occasional human error — it’s systemic.

LLMs are trained with induction. They learn by predicting the next word in a sequence of words.3 This makes them great at outputting words that sound correct in sequence. They have learned patterns for how to do this by seeing millions of word sequence completions.

Because they’re so good at outputting correct-sounding words in a sequence, their outputs will often be logically correct. For, it’s more likely that correct-sounding words are logically correct than incorrect-sounding words. A parrot that lives in a courthouse will regurgitate more correct statements than a parrot that lives in a madhouse.

This explains why Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, test-time compute and other strategies that “let the LLM think” are effective. These strategies tell LLMs to “use step by step reasoning”, the way a human would, to solve a problem. With CoT, LLMs do their best impressions of deduction. And because LLMs are good at impressions, they often guess correct lines of deduction. This makes the conclusions more likely to be correct.

It may seem harsh to call what LLMs do “guessing” — it’s highly educated guessing, to be fair. But that’s exactly what they’re doing. In fact, induction, by definition, is guessing. You use past experience, not premises or understanding, to draw conclusions. There is no “reason” why past experience will hold, or that you are extrapolating the correct conclusion from your experience. Induction is inherently probabilistic. Deduction is not.

The question is, can we get AGI from LLMs that can’t use deduction?

This could happen in two ways.

First, it could be that as LLMs get larger, they get so good at mimicking deduction that it can’t be distinguished from how humans do it. If an LLM is so good at mimicking deduction that it can discover Special Relativity using only data from before 1905 (when Einstein deduced it), then I’d call that AGI.

Second, it could be that test-time compute is a proxy for deductive reasoning. That’s what my ARC solution is doing and what o1 is doing. It could be that generating tons of educated “guesses” and intelligently searching through them is a replacement for deduction. The key question here is: how do you verify that a guess is good?

With ARC, that is easy. Run the guess on the challenge examples. But how do you do this for boundless tasks? How do you verify that an argument is logically sound or that conclusions always follow from assumptions? You could train an AI to do this, but ultimately the verifier runs into the same problem as the base LLM — it cannot inherently use deduction, which means it’s just making educated guesses. To have a verifier for AGI, that verifier may need to be AGI!

Solving ARC will be a great step towards AGI — but its solution will not necessarily be AGI. ARC is a different class of problem because possible solutions are easy to verify.

Test-time compute approaches like o1 are very useful and will continue to improve. LLMs will get better at mimicking smart, logical people. They will become more accurate and helpful. But due to the verifier problem, I don’t think test-time compute alone can get us to AGI. I think a new architecture may be needed. One that allows LLMs, or whatever their successor will be called, to use deductive reasoning.

Idea for AGI

Humans don’t think in tokens; we think in concepts. Before saying “The cat sat on the mat,” we have a conceptual understanding: a cat, a mat, and their spatial arrangement. The specific words are chosen afterward. Different phrasings convey the same underlying concept.

Current LLMs are trained to predict tokens. While they learn rich internal representations, their training is ultimately anchored to matching specific words. This is analogous to vision models trained for pixel reconstruction: they may develop edge detectors and object encoders internally, but their optimization criterion still centers on pixel-level accuracy rather than feature quality.

This insight motivated Yann LeCun’s Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture (JEPA). Instead of:

Input → Encoder → Features → Decoder → Predicted input (judged on pixel/token accuracy)

JEPA does:

Input → Context Encoder → Features → Predictor → Predicted Features

Input → Target Encoder → Target Features (to compare predictions against)

A key innovation in JEPA is that it optimizes predictions directly in feature space, not pixel space. The loss function compares predicted features to target features, emphasizing the quality of the learned representations rather than merely reconstructing pixels or tokens.

This idea could be adapted for language models by using current LLMs to identify conceptual segments in training text, then masking these segments and training the model to predict their feature-level representations from surrounding context.

By optimizing directly in feature space rather than token space, we align the learning objective with what we actually care about: coherent manipulation of concepts. While current models develop rich conceptual representations internally, they're only optimized to predict tokens — any conceptual understanding is incidental to that surface-level task. When we instead make concept-level predictions the actual optimization target, we directly optimize for what deduction requires: the ability to understand necessary relationships between abstract concepts. By making the model's success contingent on accurately predicting how concepts relate and transform — rather than just predicting tokens — we optimize for the very capability we're trying to build.

Just as human thought operates at a conceptual level rather than fixating on the particular words used, guiding models toward conceptual reasoning could represent a vital step toward more robust and general artificial intelligence.

Appendix

How to Improve My Method

Dynamic Evolutionary Architecture

Instead of using fixed generation limits, the system should adapt based on performance:

Terminate lineages that show no improvement after a few generations

Allow promising lineages to continue evolving when accuracy improves

Start over from Generation 1 if no lineages are improving

My current 4-generation limit was chosen for the ARC time/budget constraints (12 hrs, $10k max). With a dynamic architecture, you could allocate resources more efficiently.

LLM Model Diversity

I did a lot of testing. I found the latest version of Sonnet 3.5 to be the best at reasoning and coding. However, often o1 (preview and mini), GPT 4o and Gemini 1.5 Pro would solve challenges more efficiently than Sonnet 3.5. This is not unexpected. Each model has a different architecture and was trained differently. Sometimes, the core knowledge needed to solve a challenge is more readily available in Gemini’s weights.

Using a variety of frontier models, each with unique “brains”, would have likely improved performance. Getting diverse transform functions is important to fully explore the solutions space.

Prompt Diversity

I tested a bunch of prompts and examples to put in the prompts. I found different CoT prompts performed roughly the same. That is, changing the wording around how the LLM should reason or what <reasoning> tags to use doesn’t change the result in a meaningful way4. I ended up using one of Ryan’s CoT prompts with a few tweaks.

The example(s) to include in the prompts matter more, as expected. If the solution requires a vertical transformation, including an example with a similar transformation will be useful.

I tested a lot of examples and found the one that worked the best the most times. I use this example in every prompt.5 This is not optimal. There are two approaches that would be better:

Use a rotation of many examples. Adding prompt diversity lets the LLM search more of the solution space and can nudge the LLM to the right solution if the example is relevant.

Categorize the challenge and use a few examples that are known to be effective at that challenge. Or, predict which core knowledge will be needed and retrieve the examples of that core knowledge.

Finetune LLMs

I think there’s a reasonable chance ARC could be solved if you fine-tuned Sonnet 3.5 on a 10,000 diverse, correct CoT solutions for the train and eval sets — assuming all of the core knowledge necessary to solve ARC is in those sets.

With fine-tuning, you wouldn’t even need to give examples in context. Sonnet 3.5 could pull core knowledge (in this case, CoT for creating grid-solving Python functions) from training.

You could get the many training examples by running my program on ARC thousands of times, fine-tuning the model on each correct output. For the challenges it still can’t solve, you may need to hand-write the answer for fine-tuning.

1.1

The algorithm runs two tracks simultaneously: a single-parent track (Track A) and a pooled-parent track (Track B).

Track A (Single Parent):

Initial Generation: Generate 250 transform functions (50 + 200)6

If any solve all examples perfectly, select the best two and stop

Second Generation: Select top 10 functions, generate 10 offspring each

Third Generation: Select top 5 functions, generate 5 offspring each

Fourth Generation: Select top 5 functions, generate 5 offspring each

Track B (Pooled Parents):

Initial Generation: Same as Track A's initial 250 functions

Second Generation:

Select top 5 functions

For each example, find 3 functions that solve it best

Combine these into pooled prompts

Generate 5 offspring from each pool

Third Generation:

Repeat the same pooling process with top 5 functions from previous generation

Generate 5 offspring from each pool

Final Step: Take all functions generated across both tracks and all generations, select the two best-performing ones as final solutions.

2.1

I have two versions of CoT I use. For my submission, I used Version 1 since it has ~1/2 the number of tokens and I wanted to make sure my submission ran on time and budget.

Version 1 (taken from Ryan’s submission)

Version 2 (taken from Harish SG)

I tried a ton of CoT prompts and made lots of updates to existing ones. I found that for the frontier models, it didn’t matter much. Once you get them to reason step by step, the accuracy doesn’t change meaningfully.

2.2

This is how the LLM responds to my CoT prompts. As you can see, it does a convincing job of imitating reasoning.

2.3

The full system prompt:

2.4

This is how I feed in examples to the LLM. I cut off the image_urls for brevity.

2.5

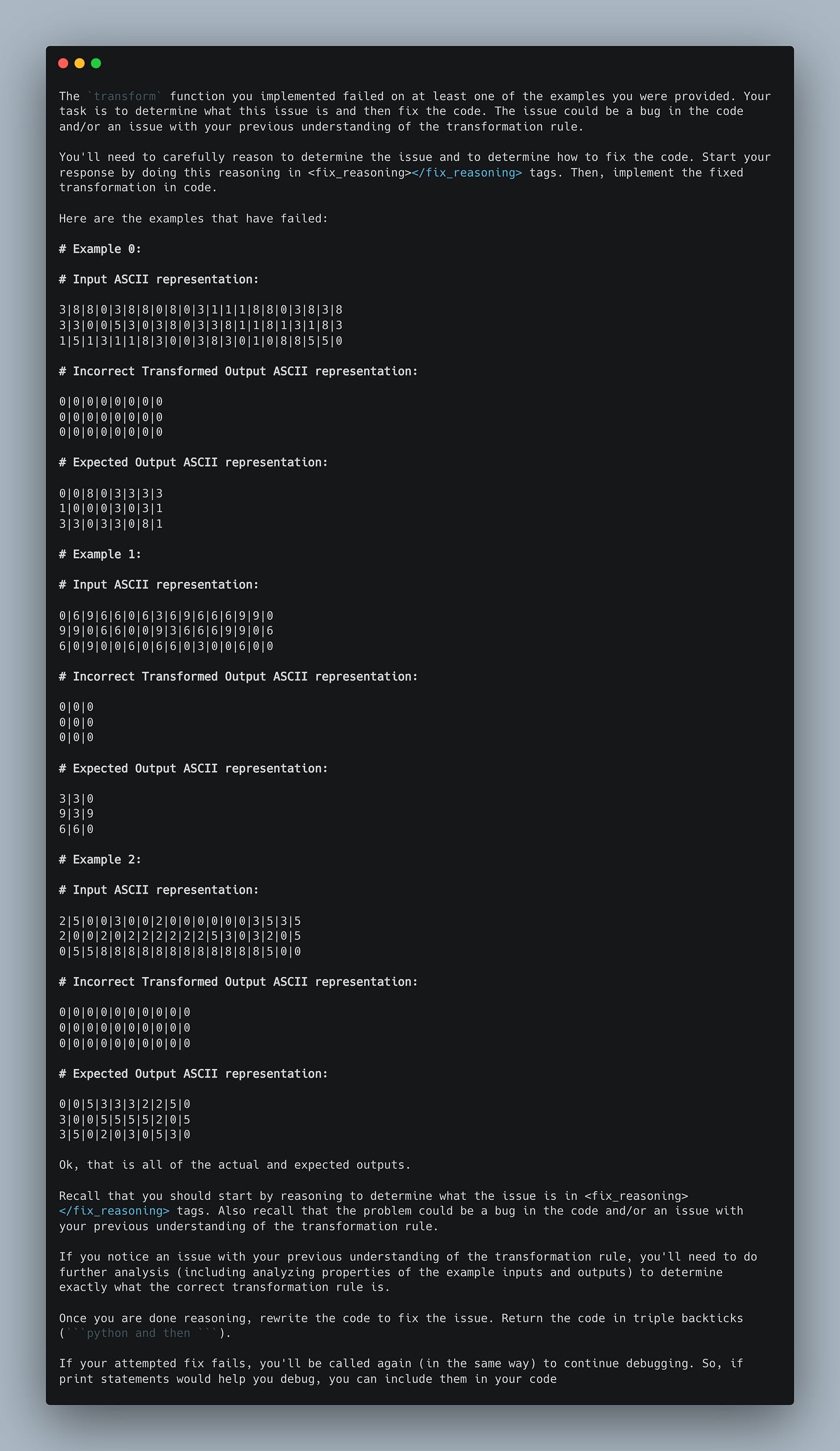

This is what a revision prompt looks like:

2.6

The pooling prompts are too large to show here but you can download a full example:

ARC has two leaderboards: the public leaderboard and the private leaderboard. A program that uses the internet, like the Anthropic or OpenAI API, is only eligible for the public leaderboard. So, my program is only eligible for the public leaderboard. You cannot win prize money for public submissions. You can read about it here.

Technically, you take the two fittest functions that generate unique output grids for the final solution, since you submit two attempts per challenge, and it would be a waste to submit the same output grid for both.

Sure, technically next token. But conceptually it doesn’t actually matter if it’s tokens, characters, words, sentences, etc… it’s still through induction.

However, testing with a large enough sample size is expensive and I could only do this so much within my budget (3k). I’m sure my prompt is not optimal but I’ve found it to be good enough.

Technically I use two examples. One example is for when the input → output grids don’t change and one is for when they do. I got this idea from Ryan.

The reason I have this 50 at the beginning is because some easy challenges can be solved outright with 50 tries. In these cases, it’s important to solve them quickly and not waste any more time or API calls on them. If the first layer were simply 250 API calls, then, for easy ones, 200 calls would be wasted. The trick is to find a balance between speed and cost. Remember that all API calls for each layer are run in parallel.

Thank you for the fascinating writeup!

This ARC “solution” isn’t really intelligence — it’s just leaning on how good LLMs already are at spitting out Python. The fancy loop around it is basically trial-and-error: throw a bunch of functions at the puzzle, keep the ones that fit, and ask the model to tweak them. That’s clever engineering, but it doesn’t get us closer to machines that can actually reason. If someone came up with a single killer prompt tomorrow, this whole setup would be pointless. It’s more of a hack than a step toward real understanding.